Shadow for a Day in the System

16 April 2024

Students will spend time shadowing in a library that uses an automated circulation/OPAC system. While you have all used the student search side of a circulation system, many functions are available to the information professional. During this shadowing experience, you will explore some of these features. Different systems have different features, and different libraries will allow observers (such as yourselves) different levels of access. You should explore the OPAC and discuss the system's features with the librarian you will visit. Our patrons guide us – if you work in an elementary school library, the processes are different than in a college or university library. Think about how the context guides what is happening, what you see, and what is taught. You will likely not be allowed full access to all records, as patrons' privacy is important. For tasks you cannot complete yourself, you should discuss the task thoroughly with the librarian so you come away with an understanding of how these tasks are performed.

So, strictly speaking, my time with this assignment involved little, if any, shadowing. There were two library systems that I had identified as prospective places to shadow at: Prince William Public Library, which I had absolutely no interaction with as a patron or student until recently; and Farifax County Public Library, which I figured I could get into reasonably easily due to previous experience there. Both of these fell through for their own reasons, leaving me to virtually flit around the system I currently work at, Central Rappahannock Regional Library (CRRL).

And yet! Despite the incorporeality involved, I still found this assignment quite enlightening, since other than the completely new aspects I exposed myself to, I had to delve into some of the features I had otherwise ignored over the year and a half I’ve familiarized myself with CRRL’s processes and procedures. Perhaps this isn’t as insightful than learning about an entirely new system, but describing everything at once makes all the links in the chain that is circulation that much easier to parse.

So, to begin with the basics: CRRL’s primary software is an integrated library system called Horizon, application version 7.5.164.22 and database version 7.5.164.0 at the time of writing, owned and operated by by SirsiDynix. Depending on how familiar you are with UI designs from around the turn of the millennium, your first impression will probably be the same as mine—"this ILS looks really old.” And you’d be absolutely correct—while I’ve yet to get an answer from someone at the system who knows for sure, according to libraries.org, CRRL first began using Horizon two whole decades ago in 2001 (Breeding, 2023).

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon startup screen [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

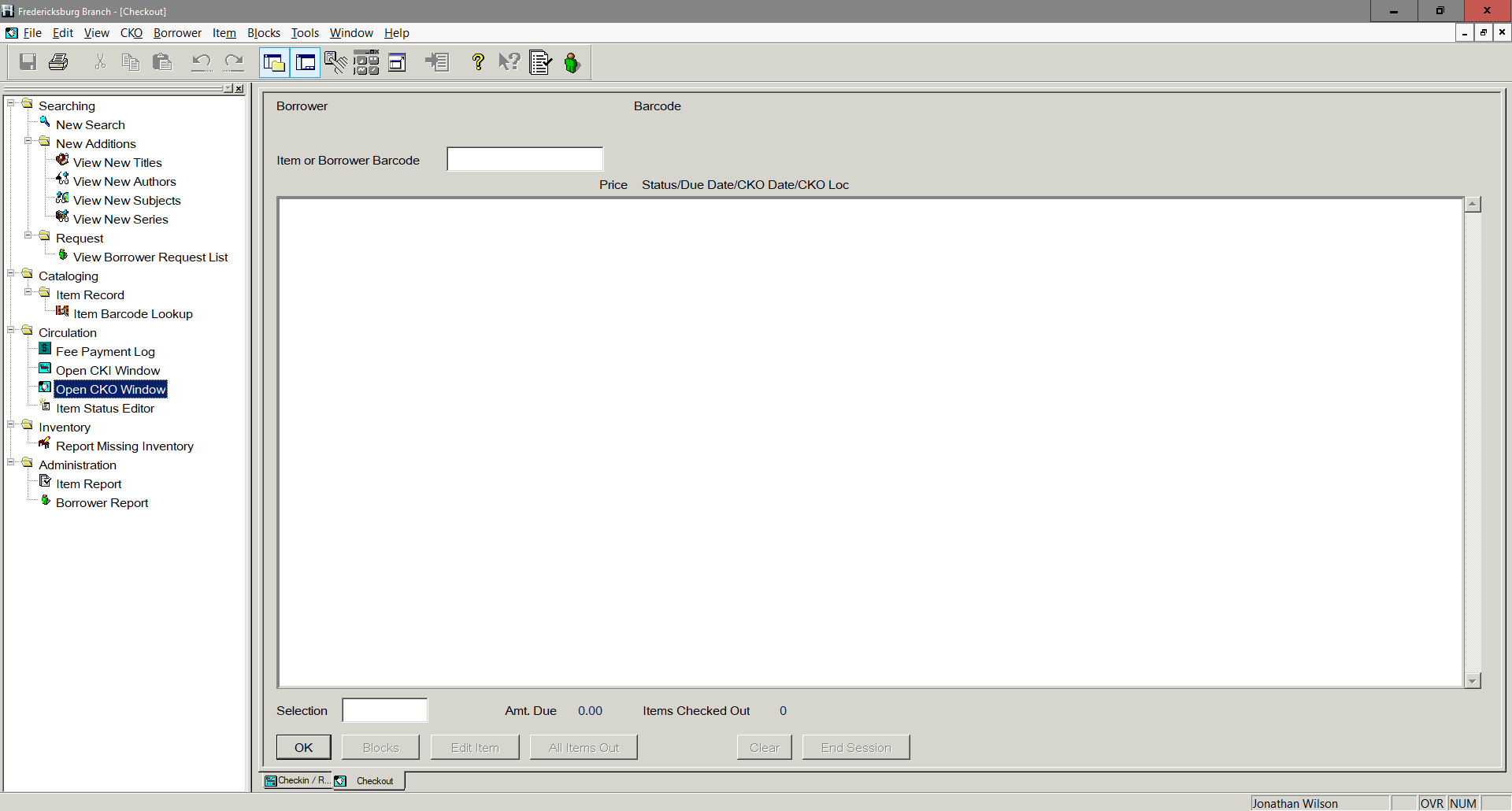

Anyway, Horizon retains all the particularities of the era, including a UI that is navigated pretty much like a file browser. The screen at startup, pictured above, is blank and seemingly unusable—almost incomprehensibly so, if the navigation bar on the left wasn’t enabled by default. Selecting one of the labelled folders by mouse or keyboard opens up the module subfolders nested within, and selecting a process will open it within the main window.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon ready for use [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

For a lowly clerk such as myself, 5 modules and 14 different processes are available to me, allowing me to search for materials, view patrons' hold lists, perform...some catalog-related barcode searching, check items in and out, change the status of items without circulating them, pull up lists of items that've ever been lost, or just generate lists of specific items or borrowers in the system.

What suite of functions are available a given account depends on who the account belongs to—not only do circulation supervisors have access to more processes in some of the above subfolders, including the ability to run reports, they can also use a whole extra module for "Serials," which I'm assuming is for processing magazines.

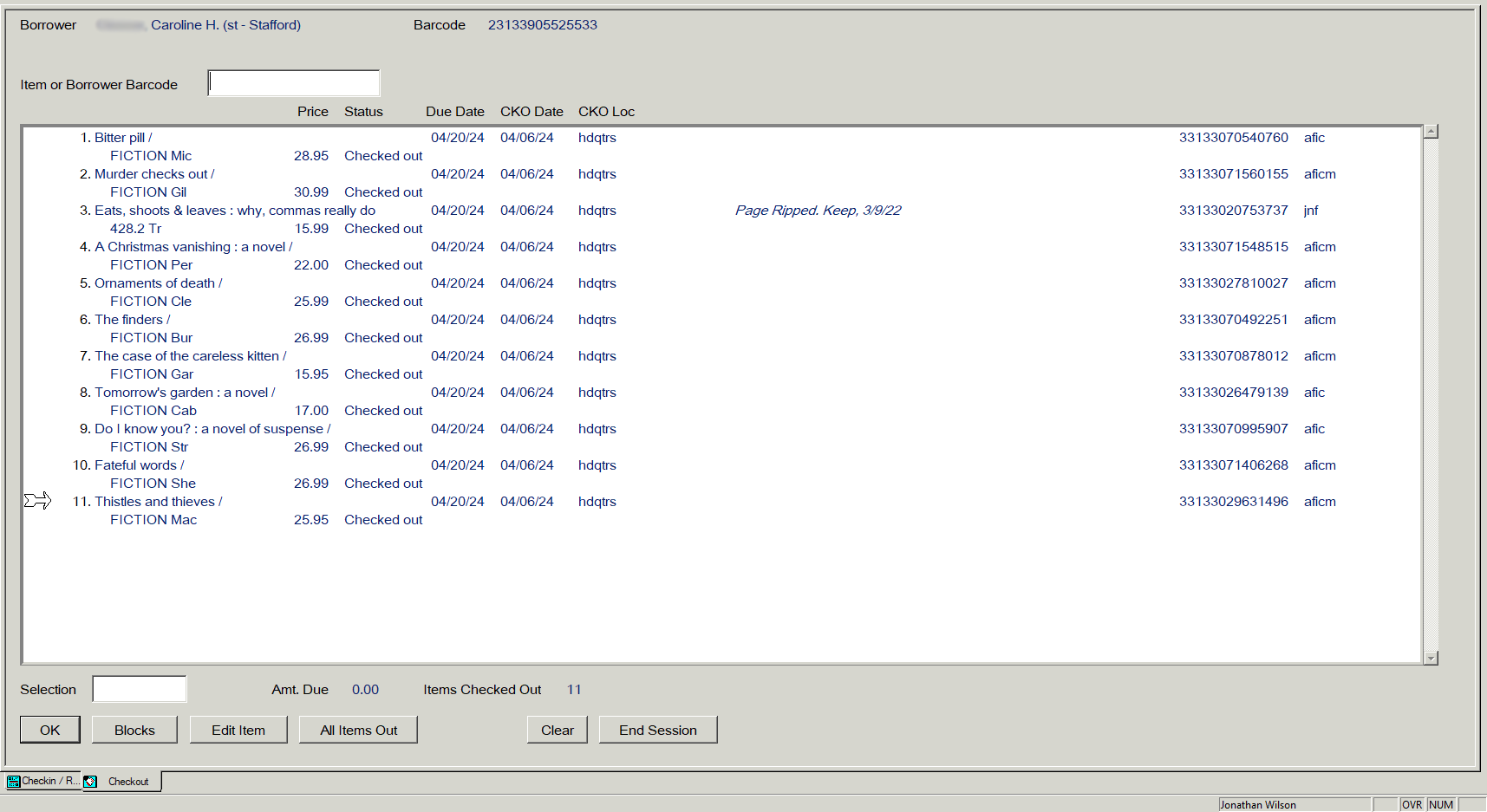

Anyway, of the couple dozen processes I've gestured towards, I only use about four in my daily duties as a clerk, which, of course, almost entirely revolves around most libraries' bread and butter: checking items in and out. It's a simple process: open up the requisite window, retrieve a borrower's account by searching records their barcode, then scan the circulating material. Since the scanners themselves are programmed to just retrieve whatever numbers are embedded into the barcode and press Enter, this can also be done through manually typing in the numbers. The only time that ever comes up, though, is when an item phased out of the system is returned—there isn't much of anything technical involved in the basic process, otherwise.1

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon checkout screen [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

The vast majority of items in CRRL's conventional floating collection—books, audiobooks, library of things—are checked out on a two week basis, while DVDs are checked out for just one week at a time. Once an item is overdue...nothing happens, really, save a customer getting emails about the overdue item(s) in question. At least not immediately, since overdue fines on all materials were waived at the beginning of last year. When an item goes to lost after 90 days, though, is when there are tangible procedures involved, enough that there's a whole flowchart depicting the possible sequence of events a lost item and the borrower's account go through. Of course, the process is automated so that there's only a trio of conditionals to remember.

Lost items add a charge of whatever price is set in the item's record to the borrower's account. If the borrower returns the item in good condition, that fee is waived from their record. If the borrower pays for the item, then ends up finding the item and returning it in good condition, then they will receive a credit that can be applied to other fees on their account. If a borrower does none of these things, then after 120 days, they will receive a debt collection fee that cannot be waived under any circumstances. This process is still quite lenient, not least because lost charges can be waived after a couple years. Borrowers are blocked from checking out any items if they've accumulated $50 in fees, yet I've never seen a debt collection fee higher than $10, and there are no debt collection agencies involved, so anyone who can't afford to pay can simply wait a long while before they can eventually check things out again.2

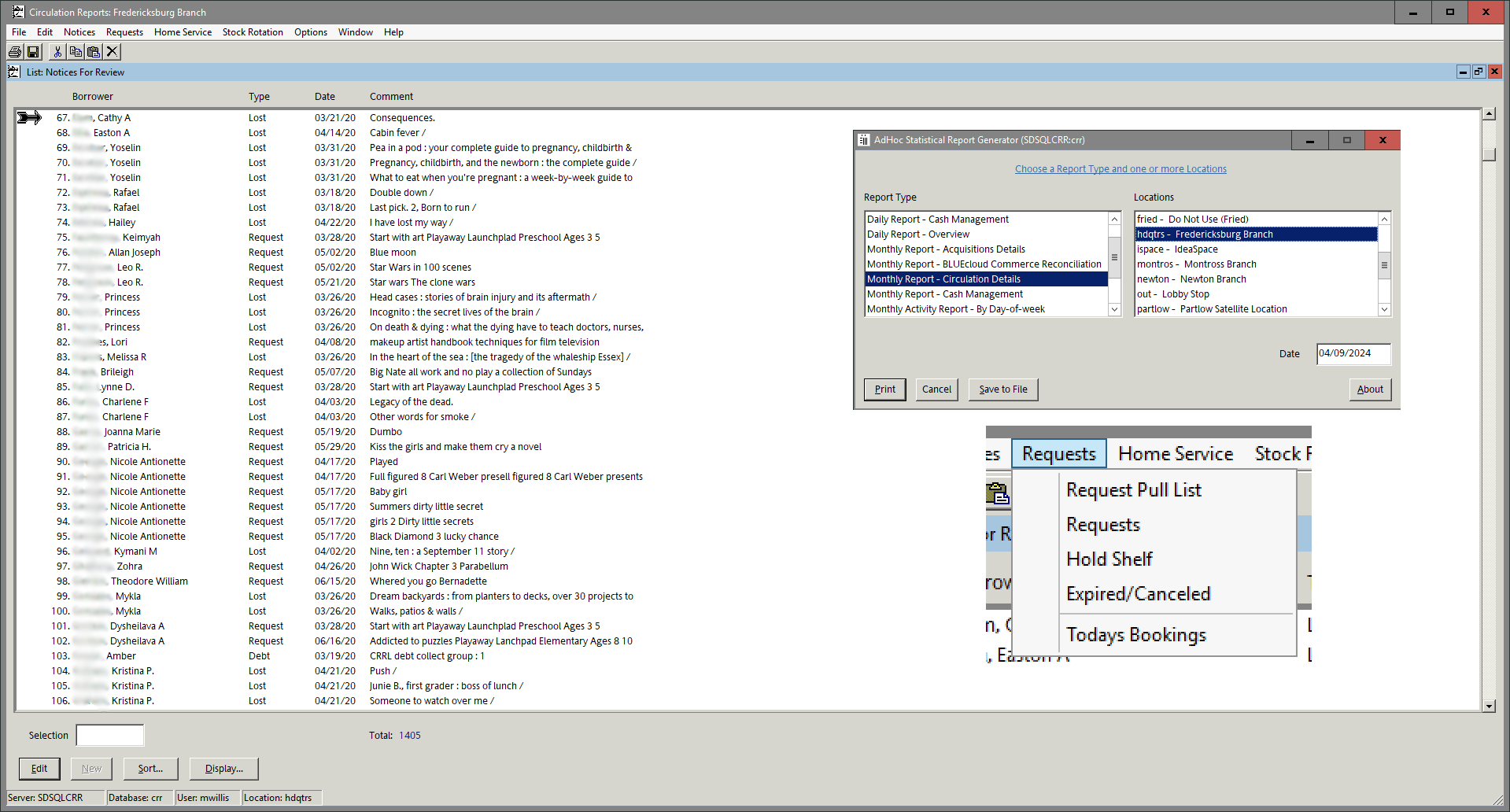

Wilson, J. (2024). Lost item records [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Since these status changes and pretty much every transaction you can think of in the ILS is automated, records are automatically compiled and stored in the system. This is, of course, where data would be retrieved to generate the hold lists that are printed out every single morning for a volunteer to retrieve from the stacks. For someone who has no exposure or intention of learning about capital-L Library work, this is the only report that has any regular relevance in their day-to-day duties—but there are tons of different reports that can be generated if one has the permissions to do so.

Wilson, J. (2024). Report selection [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Digging around in one of my supervisors' Horizon account, I found reports for active and expired/cancelled holds, items that have gone lost, items that are missing or claimed to have been returned and need to be hunted down, items that haven't circulated for 2 years and are thus considered "dead", checkins and checkouts that are sorted by type of item and borrowers' municipality of residence, cash transactions—all of which can be filtered to stats for a specific window of time or from a specific location. This isn't a full list of reports that can be made, and I'm almost certain my supervisor doesn't have access to every single one. That's probably reserved for the folks working with CRRL's backend in Collection or Technical Services holed up at the LAC (Library Administration Center).

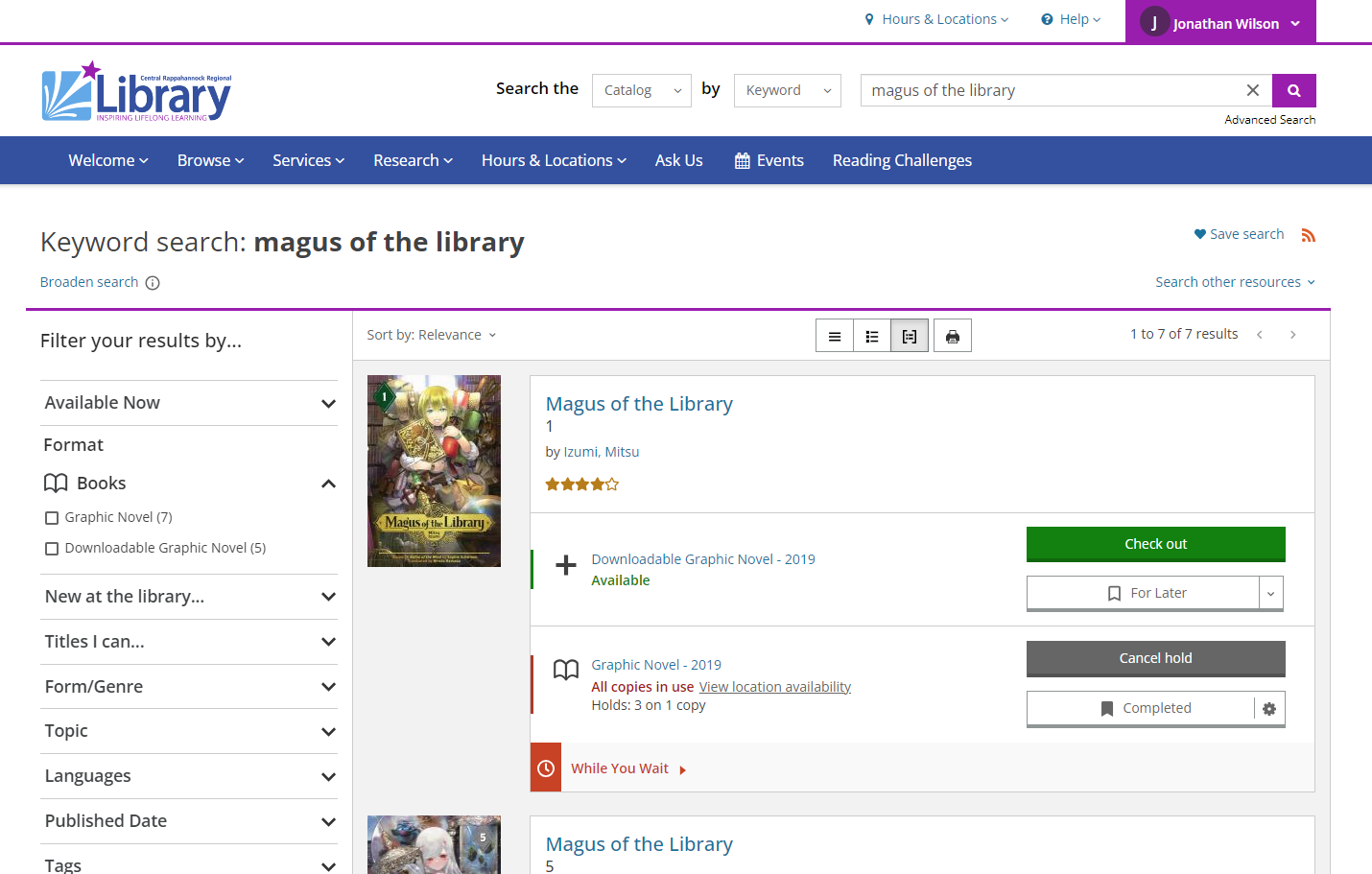

Complex as this all might seem, everything I've described might as well be background noise to most patrons, if anythihng unintended catches their attention despite the system's smooth front end. CRRL's current iteration of their OPAC is run on BlblioCommons, which is fully integrated into the BiblioWeb content management system3 from the eponymous company. Compared to most public library OPACs, BiblioCommons' design is conspicuously more up to "modern" standards, to a degree that I would normally dislike...but seeing how a fair few public libraries are still using catalogs that were modern during the turn of the millennium similar to Horizon, it rounds back into earning my favor.

Wilson, J. (2024). Searching CRRL's BiblioCommons catalog by title [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

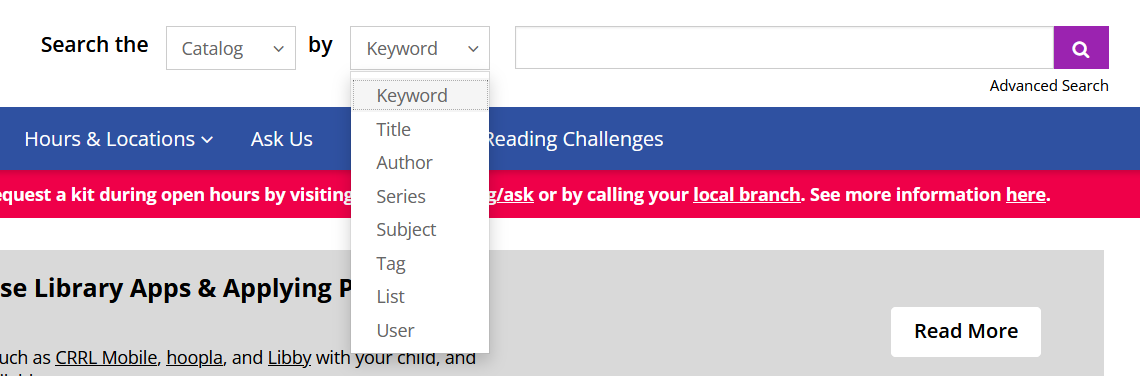

It helps that CRRL is using most of the features available on BiblioCommons to most of, if not all their extent. News updates, event listings, location addresses and contact information, databases and news site proxies and other research resources, reading challenges—if there is something that the system is doing or involved in around the region, there's probably a link to it or discussing it on CRRL's website. There's enough going on that it actually kind of crowds out the circulation features, but they still remain just as robust as the OPAC itself. The site's search bar can be used to retrieve information from individual webpages, events, or FAQs, but the default option is, of course, CRRL's catalog. Users can search the catalog by the usual parameters of Keyword, Title, Author, and Subject, but BiblioCommons also features some that are seldom seen elsewhere. The most straightforward of these is Series, but for folks who aren't familiar with BiblioCommons' interface might find the others strange: List? User? Tag?

Wilson, J. (2024). BiblioCommons search parameters [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

If you are familiar with social media, specifically those that are based around user-generated content, then you'll have a good idea of what each is. Tags are the most obvious example of these, simply brief phrases and/or descriptors added by users that they think are representative of the work, sometimes in harmony or conflict with subject headings. Users is basically what it says on the tin—BiblioCommons allows for the creation of user profiles that can be used to rate and comment on books, among other things; and if a library running on the platform has enabled it, the catalog can display content from and allow for searching of other users within and outside the current system.4 Lists, meanwhile, are just booklists, curated lists of books or other materials oriented around a specific theme or what have you, along with a short description of each item if the creator so chooses. One nice thing about BiblioCommons lists is that if a list is made by a user within the same system, then each item will have a conspicuously enticing "Place hold" button next to each item, along with information about the items availability within the system to make locating a copy almost immediate.

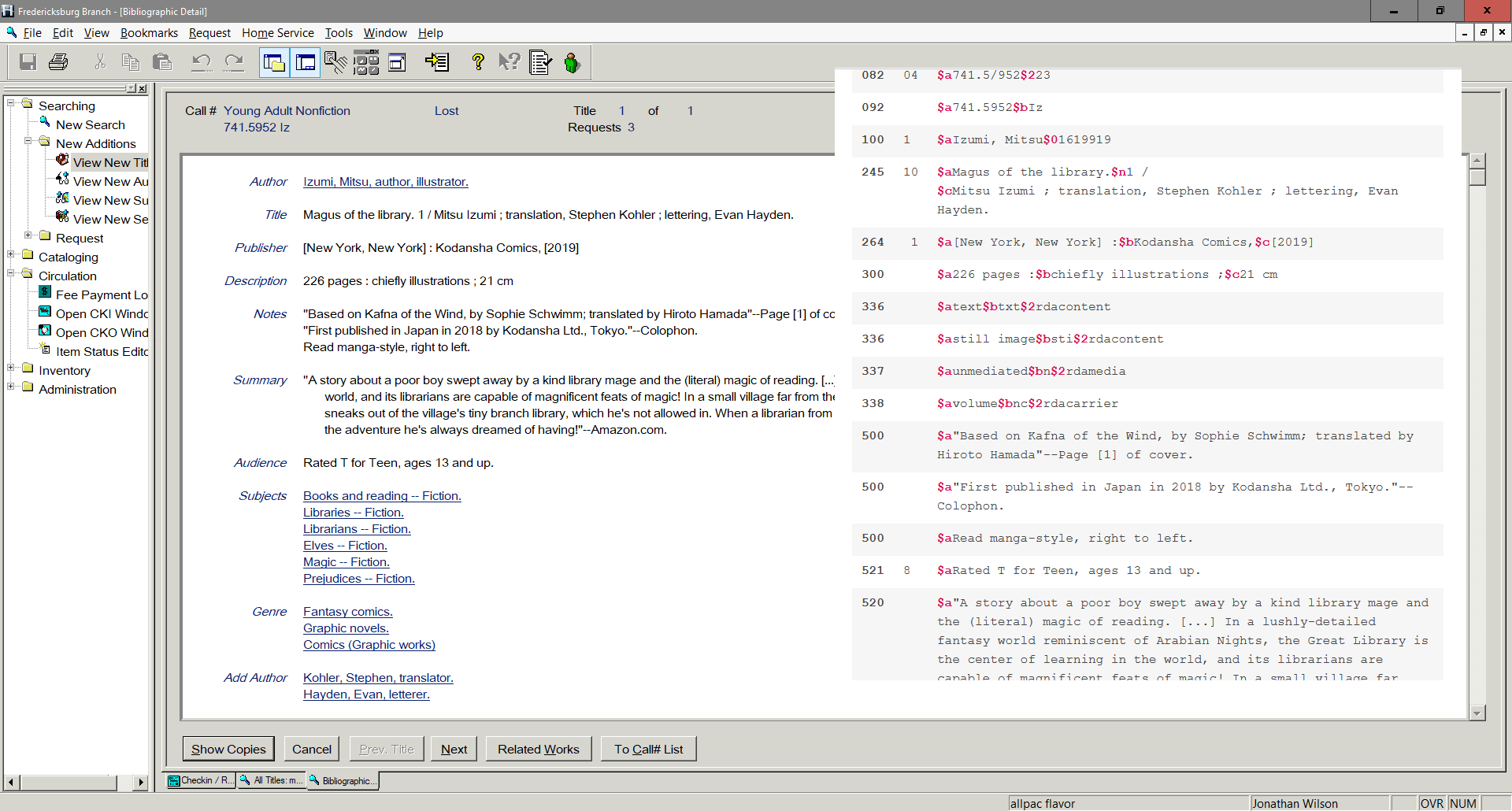

For all the bells and whistles on CRRL's front end, the records on the back end are just as plain and antiquated as the ILS they're handled in. Copy cataloging is the bulk of the encoding work done by libraries due to how digitally transmissable the library landscape has become, and CRRL is no exception. MARC records are retrieved from OCLC's gargantuan database5 through their proprietary software, edited with MarcEdit to suit CRRL's specific cataloging standards, then imported into Horizon. I wasn't able to get permission to view anything in the system's backend for this assignment, but both the records and the MARC records were still accessible through Horizon and BiblioCommons, respectively.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon and MARC records [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Ironically, unlike a lot of other OPACs, BiblioCommons practically buries a record's MARC view in its UI, along with the call numbers and subject headings and all the classification nitty-gritty. One has to scroll down to the middle of a record's webpage for a "Full details" link, then scroll all the way down to that page for "Original record"—to reach a page that seems specifically coded to not use a screen's space efficiently.6 It's almost as if these aspects are an afterthought to BiblioCommons' designers...or, maybe, to maintain its modern feel, it has to obscure any trace of the underlying code that laypeople would find incomprehensible.

In fact, for all of BiblioCommons' fancy features that patrons might not be familiar with, as far as I can tell, CRRL actually doesn't have any formal instructions or FAQ or anything resembling a "how to use our catalog" guide. This might just be an inarguable weakness—but given the enormous barrier that has long existed for anyone unfamiliar with digital technology, I think it might be fair to assume anyone who can reach the OPAC is literate enough to they intuit how the catalog works relatively easily. For the vast majority of people who aren't, they'll just keep coming into the branches to get assistance with managing their books and accounts, as they always have.

As for the actual, tangible items that records are digitally representing, none of them can circulate if the library doesn't physically acquire them in the first place. Once an item is chosen for acquisition, its life in the system begins with a simple record while the item is ordered from a vendor. Books are usually purchased from either Ingram or Baker & Taylor, two longtime library suppliers and CRRL's main vendors. Other places include Brodart, which provides rental copies of adult hardcover books if they prove popular enough, Midwest Library Services for audio/visual items—and, if an item isn't available through any other channels, Amazon. Book jackets and lamination and barcodes are usually applied by the vendors before they're shipped out to the system; once the system receives materials, catalogs them, then links them to their respective OPAC records, stickers for newness or genre/seasonal/holiday/etc. are added—then they're sent to branches for circulating or shelving. Items that remain on a shelf are ordered by an author's last name for fiction items, and Dewey Decimal number for nonfiction items—yet despite being set aside in their own places, both graphic novels and film DVDs are organized entirely by their classification number instead of like fiction.

The mechanics of every single process I've described in this essay is overseen by staff at the LAC. And as I've implied previously, outside of checking items in and out and/or putting books on the shelves, these processes and procedures and transactions are done without much understanding of the mechanics by those carrying them out. But, as I've tried to convey here, they are all quite comprehensible, if scattered—yet subsequently remarkable in how every aspect comes together into a single process. I hope this makes CRRL's circulation that much more tangible, and lends insights into how these processes work and differ at other systems.

1 ^This is almost certainly where I’m missing out on a ton of insight as to how different systems do these processes, since I have no experience with any other ILS and thus nothing to make a comparison to.

2 ^We don't tell anyone this, of course.

3 ^Content management system (CMS) is more or less just a fancy name for a website builder.

4 ^This is where BiblioCommons' UX starts seeming too like social media for my taste, but the illusion of local activity veiling a widespread reception to a given book is actually kind of nice and useful.

5 ^Try using WorldCat if you haven't already.

6 ^Here's the original record for the example item used throughout this essay—try resizing the window to see how spread out the fields are stuck as, compared to something like the MARC views from Norfolk Public Library's Enterprise catalog.

References

Breeding, M. (2023, November 7) Central Rappahannock Regional Library system. libraries.org. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from: https://librarytechnology.org/library/30081

Wilson, J. (2024). BiblioCommons search parameters [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon and MARC records [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon checkout screen [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon ready for use [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Horizon startup screen [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Lost item records [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Report selection [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.

Wilson, J. (2024). Searching CRRL's BiblioCommons catalog by title [Screenshot]. CC BY-SA.