Graphic Novel Reading Reflections

21 June 2024

Wilson, J. (2024). Graphic novels and originals read in summer 2024 [Photograph]. CC BY-NC-SA.

Beaton, K. (2022). Ducks: Two years in the oil sands. Drawn and Quarterly.

Ducks is a title that I’d seen praised with a lot of heartfelt words from people I know and respect, and while it didn’t pull on my heartstrings too hard, I absolutely understand why it resonates so deeply with people. Ducks patches together a massive scrapbook of vignettes from her pursuit to pay off her student loans, as Beaton follows the siren song of a gold rush far from her costal home to the Canadian oil sands. There, she finds herself navigating the bruising dynamics of being a woman in an overwhelmingly male-dominated environment on the edge of society, with all the themes you’d expect: sexism and gendered violence, economic precarity imposed from the top-down, the effects of living isolated environments on people. Hark! A Vagrant, Beaton’s name-making webcomic parodying historical people and phenomena of western history, features a flippant, offhand art style resembling a teenagers’ irreverence, one that is preserved in Ducks—and yet it does little to counteract the somehow solemn, pristine presentation undergirding this graphic novel.

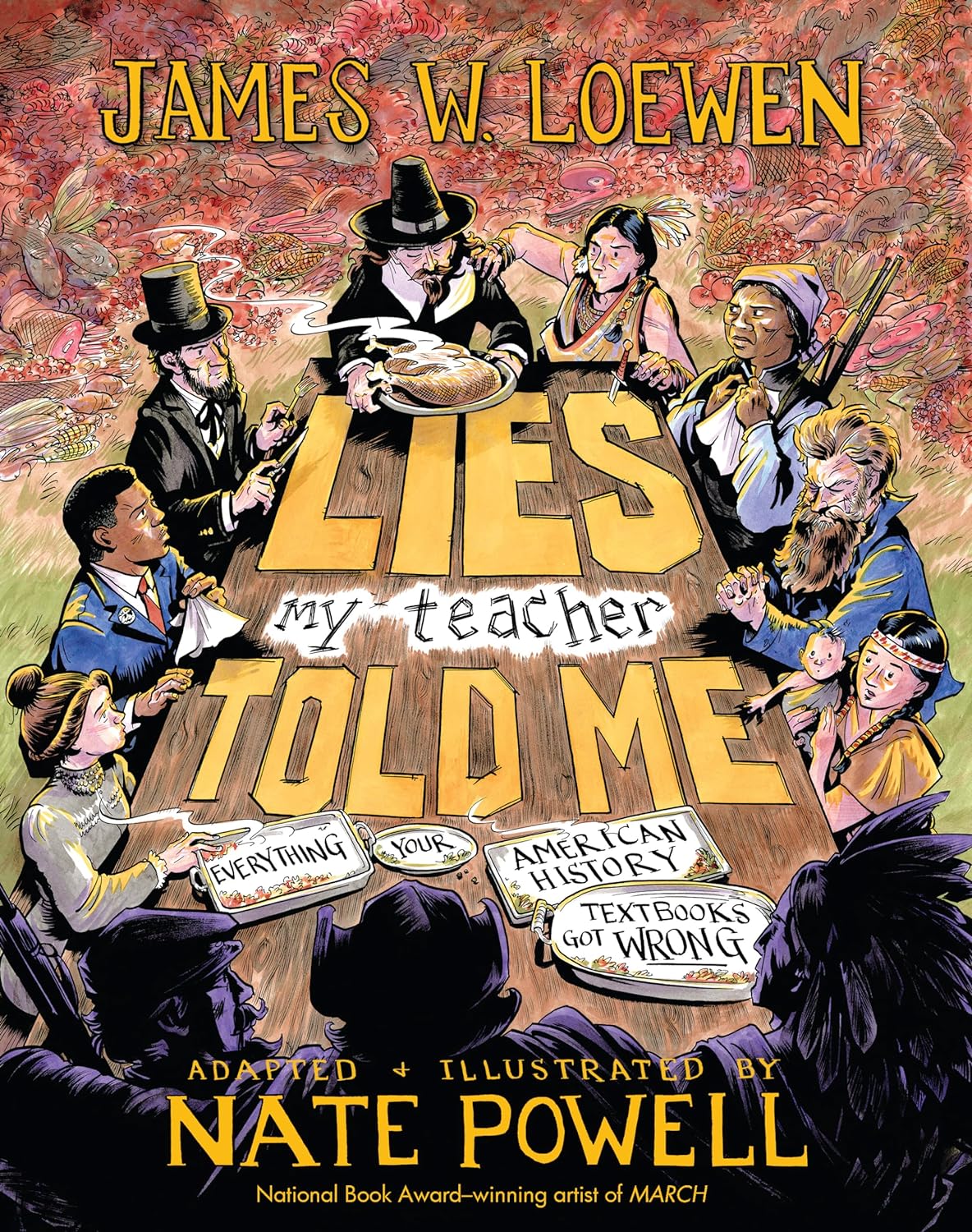

Loewen, J. W., & Powell, N. (2024). Lies my teacher told me: a graphic adaptation. The New Press.

For me, adaptations of a work generally aren’t preparation to engage with another version of that work. If there’s a book with a movie, or a novel with a graphic adaptation, picking one version of the other usually has enough engagement for me that I don’t feel the need to pick up another. The graphic adaptation of Lies My Teacher Told Me, however, is one that I’ve found to be very useful in grasping the full extent of its source material. Originally written by James W. Loewen nearly 30 years ago, the text nonfiction edition is stuffed with all the quotations and refutations and citations one would expect from a historian and professor with a career for almost as long at the time of publication. But this graphic adaptation, done in collaboration with longtime comic artist Nate Powell, takes a 446-page book cutting through the mythologies of American history peddled by the country’s educational material, and cuts it down to a little over half of its original length. The result manages to retain the essential text of the original book, while supplementing that text with faces to attach to famous and obscure names, renderings of notable places and people, visual metaphors to drive home the textual ones, and more in sequential form to augment a reader’s retaining of the material. Powell’s artwork, which wouldn’t be out of place in political satire strips, is a natural fit for historical nonfiction, to say nothing of his previous work on the award-winning March series written by John Lewis and Andrew Aydin.

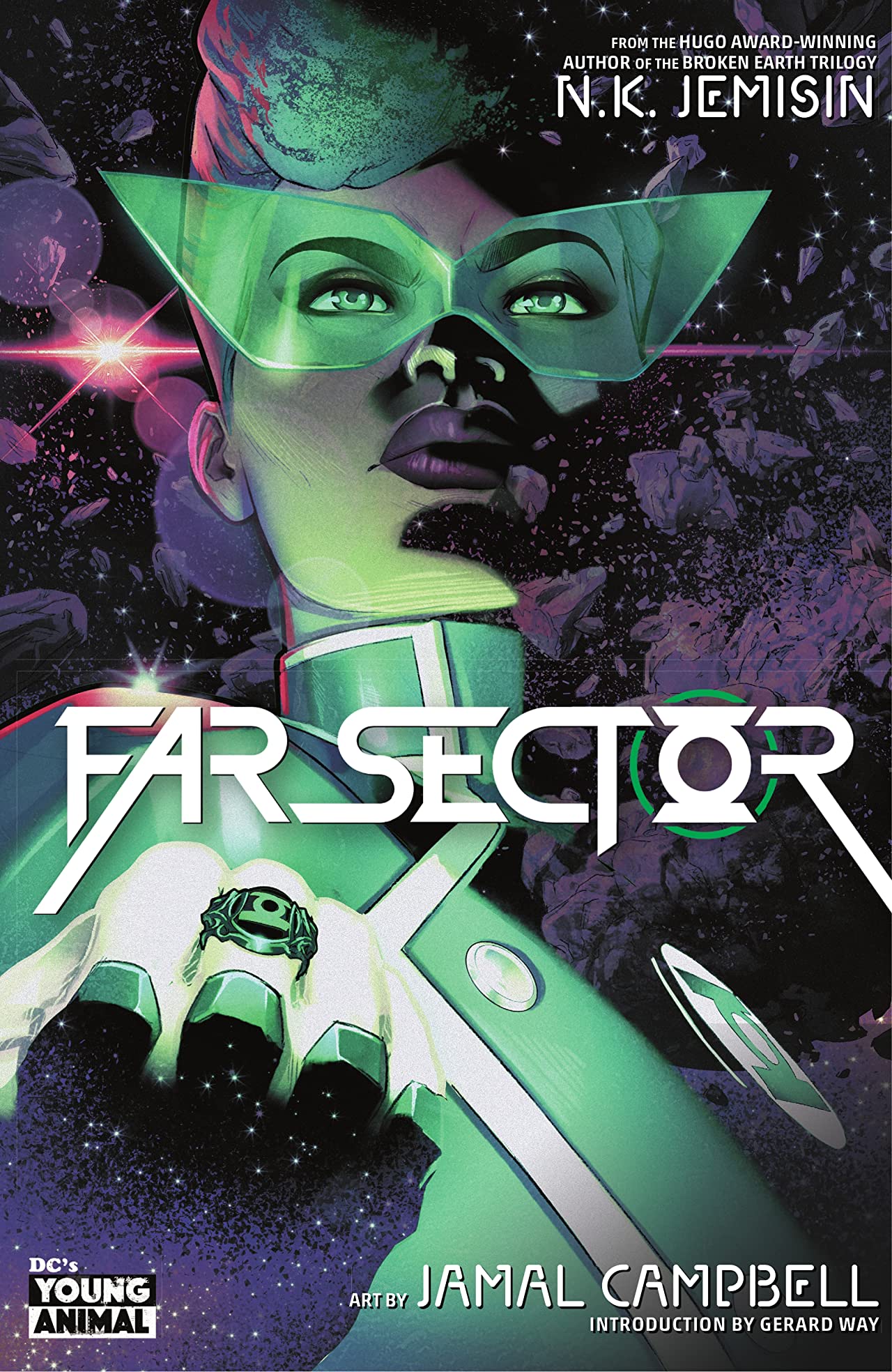

Jemisin, N.K. & Campbell, J. (2021). Far sector. DC's Young Animal.

N.K. Jemisin is one of the greatest (sci-fi) writers to ever walk the earth, so I had nothing but high expectations for Far Sector. Naturally, even for her first foray into comics, Jemisin’s scriptwriting met those expectations—and together with Jamal Campbell, soared above my expectations to create one of the few traditional, issue-based western comics that I’ve enjoyed reading. That might just be due to familiarity, as Far Sector is playing with ideas established by one of Jemisin’s past works, the short story “The Ones Who Stay and Fight.” Instead of a solarpunk future on Earth, Far Sector takes place on a the far-flung, planet-encompassing City Enduring where the series derives its name, one that has maintained an unprecedented peace for the past five centuries, a stark contrast to its complex and conflict-filled history. Of course, that’s mostly because the city implemented a genetic modification that impedes its citizen’s capabilities to even act on their emotions, much less respond to that history—but when the City sees its first violent crime in generations, plus the release of a drug capable of removing the modification for good measure, a new war threatens to engulf the entire sector. Sojourner Mullein, a rookie Green Lantern and the sole human among 20 billion nonhumans, must navigate the unrest the citizens and maneuvering of their leaders to uncover the original cause and bring justice to the City, all while contending with the notion of a peace kept through a refusal to respond to the past. Jemisin’s wry voice and speculative visions are on plain display through Jo and a cast of humanoid creatures with wildly different designs, but none of it would be nearly as effective were they not framed through Campbell’s stellar pages and style. Gerard Way, a curator at Young Animal, describes Campbell’s artwork as “modern, technicolor, and full of energy,” in the introduction, which is the perfect summary.

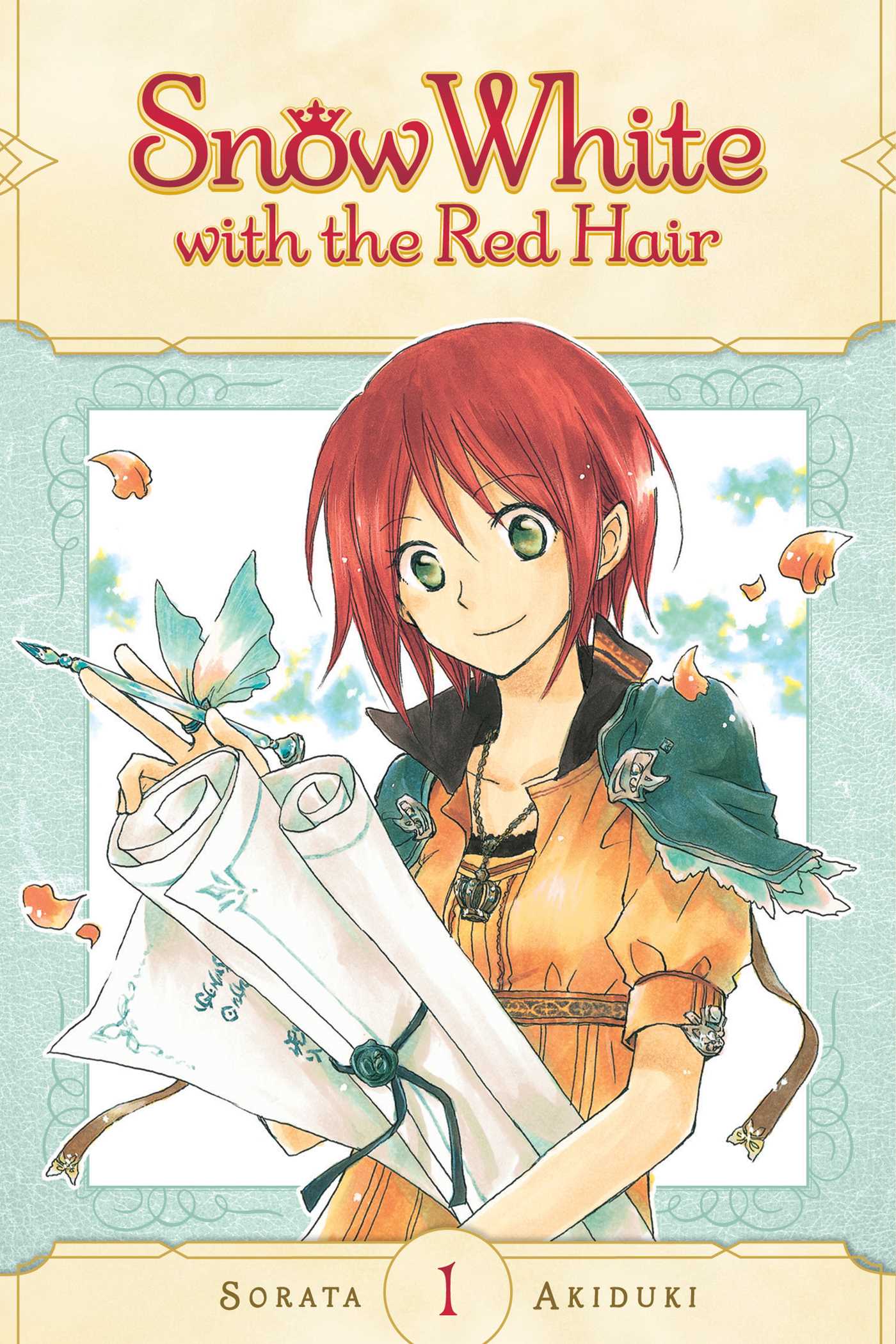

Akiduki, S. (2019) Snow white with the red hair. Volume 1. VIZ Media.

As a guy who had little interest in anything not oriented towards guys until relatively recently, I had next to no exposure to manga made specifically for girls, thanks to all the usual reasons explainable by reading any reputative work on feminism. Though I did hope that my first excursion into shojo would be more engaging than the shonen I’d largely soured on, Snow White with the Red Hair ended up falling more than a little short for very similar reasons as its boyish counterpart. That doesn’t mean that this manga has nothing to appreciate, though. Shirayuki, the main protagonist whose name is a literal compound of “Snow White," begins with her becoming the target of not ire from a jealous queen, but the covetousness of the prince of her home kingdom, thanks to her apple-red hair. Shirayuki flees into the forest, has a chance encounter with a young man, Zen. With the help of this dashing stranger, who turns out to be a prince from another kingdom, Shirayuki is able to evade the machinations of the men seeking to constrain her—and so begins her tale to carve out her own path through life…supposedly. As typical of most narratives involving an innocuously amusing meeting of a potential love interests minutes into the opening act, Snow White with the Red Hair is a fantasy romance, and any secondary intrigue is ultimately intended to dripfeed into Shirayuki’s supposed love affair with Zen. While many of the situations she finds herself in usually require Zen’s assistance by the end, Shirayuki is written with a remarkable self-assurance, showing indignance to the men around her and devising ploys to escape her binds all on her own. Akiduki’s entire body of work is published in shojo magazines, so her artwork is quite typical for the genre—lots of fragmentary panels of areas and everyday objects and characters’ eyes and/or other body parts common across the manga landscape, and this peculiar use of these glowing motes and other particles to evoke emotional crescendos, among other techniques (McCloud, 2006, p. 216).

Wibowo, J. & Wibowo, C. (2024). Lunar boy. Harper Alley.

Lunar Boy, while a juvenile neo-Indonesian sci-fi graphic novel about a trans boy from the moon with a lighthearted plot typical of escapist queer stories, is something I knew was very intentional about its place in that context. In a comic posted to social media two months before Lunar Boy’s publication, the authors lament the shape people of color usually take in these stories: stripped of cultural specificity, the intersection of their identities, and the histories of the communities that shaped them. To that end, Lunar Boy was created to be a wish—not only for the good future that those unsatisfied with our present yearn for, but specifically one where the marginalized are able to live out their own traditions (Wibowo, J. & Wibowo, C., 2024). What’s rather ironic about things, though, is that I genuinely do not think you need to know much about queerness or Indonesian culture to get something out of Lunar Boy. There are a couple of emotional beats specific to the transgender experience that might fly over unaware heads, but are given clarity later on. The Indonesian steeping might seem like a taste that needs to be acquired prior, yet as specific as the setting is, Lunar Boy is ultimately about the selfsame social challenges everyone faces. Indu, the protagonist and eponymous boy born on a moon, is coaxed away from his lunar cradle through a chance encounter with an astronaut-turned adoptive mother, and despite of the warnings of his biological parent. Though the community aboard his mother’s spaceship are unquestionably supportive as Indu clarifies his identity, a marriage and career change find Indu settling with his mother on New Earth. And as a planet presumably down the timeline from ours, the same old pressures and prejudices persist. Contending and changing and seeking closure is too much to ask for Indu—but the moon, ever the watchful parent, offers Indu an opportunity to return home on the new year. He accepts—and shortly after, Indu begins to accept his home; by finding community and connection with the people that he can, either through shared queer identities that have persisted through the ages, or by reaching over gaps in language and grief. Lunar Boy’s art style, akin to an animated cartoon put to print, is specifically rendered to emphasize the latter: scenes off-planet and when the moon calls out to Indu are drenched in cool blues and shadowy purples to evoke the chilling stasis of space, while New Earth seldom strays from warm earthen tones for a life that’s sometimes burning, but always capable of remaining balmy.

Larson, H. & Mock, R. (2021). Salt magic. Margaret Ferguson Books.

Having only heard Hope Larson’s name a few times with that vague aura of acclaim surrounding her and Rebecca Mock’s not at all, I had no idea what to expect from Salt Magic—but in reading it, I found a pretty solid graphic novel. That’s…kind of it. Quite an undersell, especially considering that this one won the Eisner for Best Publication for Kids in 2022, but I dunno—while Salt Magic doesn’t seem to be doing anything revolutionary by my estimation, I found it nonetheless compelling for how well-crafted a comic it is. Of course, it is the duo’s third outing together into the annals of America after a duology of graphic novels set in the late 19th century, this one moving up to the turn of the 20th. Salt Magic stars a Vonceil Taggart, a rambunctious girl whiling away on her family farm for her fun-loving older brother Elber to return from World War I—who is much changed from brother he was upon his departure. Greda, a secret salt witch lover’s fling from his time in Paris, follows in his wake, and quickly comes to the same realization upon insisting he return her love. In retribution, Greda curses the Taggart reservoir unless Elber agrees—and so Vonceil takes responsibility, embarking upon a quest to confront Greda and lift the curse. Be it the “Magic” in the title or something else, Greda’s salt magic so casually invokes an association with fantastical elements that the fairy-tale creatures and motifs that increasingly appear throughout seem so natural to the story as if they were real. Even still, Salt Magic ends up being about a very real theme: the losing and subsequent searching for companionship, be that a person who grew up and changed into someone else, or just simple, obsessive loss.

Martín, P. (2023). Mexikid: A graphic memoir. Dial Books.

As I started writing my reflection to Mexikid, I came to the realization that I can’t remember the last time I’ve read a juvenile comic about a boy that is also written by a man? This is an incredibly specific and strange thing to admit, but my taste in media has shifted so far in a direction that isn’t just upward that reading Martín’s thoroughly prepubescent boy memoir of his family’s journey into Mexico and back felt like staring at a shore sitting on a miles-away horizon. Which doesn’t mean my reading of Mexikid was at a disinterested remove, either. Though the webcomic that preceded the physical book is mostly made of black-and-white strips, the full rendition of Martín’s bright, retro-tinged art style goes hand-in-hand with the boisterous escapades and sibling badgering and the references to pop culture and superhero-comic sequences. And amidst all that cheeky humor and frenetic energy, Mexikid still manages to stop for some contemplation, too. A trip to retrieve an aging grandparent from their native country they still have roots is obliged to grapple with the life they’ve lived and the land that made them; or in Mexico’s case, the political circumstances imposed upon them by their northern neighbors. Martín handles these moments well, nodding towards the implications while simplifying their presence in ways that middle school children can still grasp.

Tolkien, J.R.R., Dixon, C., & Wenzel, D. (2012). The Hobbit: an illustrated edition of the fantasy classic. Dey Rey.

Going into an adaption of a work in a genre infamous for doorstopper-size novels by the de facto father of that genre, I knew condensing The Hobbit into a graphic novel would come out a little rough around the edges. Some of those edges made it too rough to stick out, though—when going from a medium where lengthy tomes are much more permissible to one where things are generally expected to be succinct and snappy, the result will generally hew towards the latter. Chuck Dixon, longtime superhero comics writer and scripter for this adaptation, did his best to achieve an equilibrium, cutting out most of the omniscient narrator’s voice that was so essential to the original, along with all the little commentary and anecdotes and ditties that give it extra character and whimsy. Meanwhile, any narration or dialogue that is retained is copied word for word in all its antiquated length. This is somewhat accommodated by the smaller text, but in my impression, shrinking the text does nothing to reduce the inherent density of Tolkien’s prose, which left the reading experience akin to reading the text, looking at the art, and mentally stitching the two together. The artwork, at least, is quite fitting for The Hobbit’s lighthearted tone compared to its sequels, which is done by David Wenzel, primarily known for illustrated editions of classics. Sticking to rectangular, symmetrical paneling keeps its presentation straightforward compared to complicated and zanier devices of today, with cartoonish-leaning artwork barely a stone’s throw from superhero comics of the time, yet Wenzel’s watercolors and lack of sharp edges convey a gentleness befitting the intended juvenile audience of the original book.

Weir, I.N., & Steenz. (2018). Archival quality. Oni Press.

Archival Quality is, unfortunately, the only title here I feel is undercut by one of its most fundamental aspects. Which is a real shame, because the story that unfurls in its pages is one that I was practically guaranteed to resonate with me. Celeste Walden*, struggling to hold herself and a relationship to her boyfriend together after a crushing mental breakdown at her library job, finds herself searching for a new one even more orderly than the last. The job she finds, an archivist position at a local history museum, is anything but. There’s an onsite apartment she has to live in, her hours run through the middle of the night—and then there’s the supernatural forces making noises and moving things around and giving Cel vivid dreams about of a person she’s never seen. And though her colleagues find nothing bizarre about it all, the strange phenomena only increase with their severity, pushing Cel to uncover the dark past buried within the museum, and how they echo in her own present life. That dark past, of course, is none other than how people with Cel’s selfsame issues were treated in a bygone era and how those notions persist today—something that is perhaps even more resonant in an era where exponential awareness hasn’t done much to collectively improve things. As resonant as the narrative is, Archival Quality’s visual presentation doesn’t feel equally so—not necessarily hurting the story it’s telling, but not enhancing or adding to it, either. While Steenz has a body of illustration work with an array of mediums and techniques, she renders Archival Quality in her signature, heavily cartoonish art style, with offhand, intentionally uneven lines and bright hues coloring common symbols to represent the finer features of the human body. Definitely suitable for most stories about young people in the present day, which makes up the entirety of Steenz’s comics work—but for a book concerned with connecting historical threads, the artwork would be better served by leaning into techniques that are evocative of those bygone years.

* I refuse to believe it’s a coincidence that both Archival Quality and the hit videogame Celeste were released within three months of each other given that they’re variations on the exact same subject.

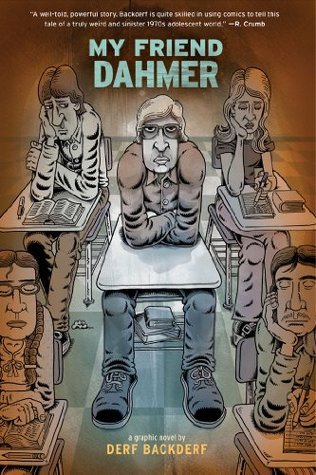

Backderf, D. (2012). My friend Dahmer: A graphic novel. Abrams ComicArts.

If I had a nickel for every title I read this semester about American youths being failed by their authorities, whether implicitly or explicitly, I’d have two nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it is strange that there’s two of ‘em. Industry reviews of My Friend Dahmer describe it as a “tragic chronicle” and a “hard-to-believe autobiographical story” about one of America’s most notorious serial killers, but Backderf isn’t subtle in asserting that the 70s suburbia culture played a significant role in creating an “inhuman monster” out of “the loneliest kid [he] had ever met.” As someone who grew up alongside the latter, Backderf’s account is the story of the former, indirectly depicting only a single one of Dahmer’s murders and only at the very end. Of course, it’s not like any of them were necessary to create its chilling effect. Backderf’s signature art style, with its bold lines rendering bizarrely-proportioned, head-heavy bodies, feels resemblant of political satire. With such a heavy subject matter though, My Friend Dahmer is very much not a laughing matter—and the juxtaposition of the art and subject pervades the book with a constant unsettlement, the threat of Dahmer’s future violence seemingly lurking behind each and every page.

References

McCloud, S (2006). Making comics: Storytelling secrets of comics, manga and graphic novels. William Morrow.

Wibowo, J. & Wibowo, C. [@jesncin]. (2024b, April 2). Lunar boy and queer escapism. [Images attached]. Cohost. https://cohost.org/jesncin/post/5388230-lunar-boy-and-queer

Wilson, J. (2024). Graphic novels and originals read in summer 2024 [Photograph]. CC BY-NC-SA.