Graphic Novels Discussion #2: Nonfiction

28 May 2024

Read both of the nonfiction titles you've chosen and answer the following questions.

• Tell us the story of how you found your title/material (BRIEFLY). What resources helped you pick your material?

• What is the title/material’s appeal? How does it appeal to the target audience? How can you tell what the target audience is?

• If this is a diverse title: Identify the communities to which the primary character(s) belong(s). Does the author belong to the identity depicted? If not, how accurate is the portrayal to the best of your knowledge? Seek out reviews, blogs, etc. to help with this assessment.

• If you've read/seen the original, what differences are there between the book you chose and its adaptations? How much did the story change? Was that a reasonable change or not?

• What made this particular book a good (or not!) choice for adaptation?

• Is there a nonfiction topic or person's life you'd like to see adapted? Why or why not?

Wilson, J. (2024). Nonfiction graphic novel selections [Photograph]. CC BY-NC-SA.

When I think of nonfiction books, I generally don’t imagine anything that would easily translate to a graphic novel. In lieu of the library of techniques fiction can use to make their intended emotions more felt, nonfiction’s primary purpose is to convey information in a plain, standardized format, usually almost entirely if not exclusively through text. McCloud (1993), tracing the divergence of words and pictures in media over the centuries, describes how the pictorial and symbolic languages of prehistoric cultures become “more specialized, more abstract, more elaborate” throughout modern times to become the abstract, sound-based text that we all read and sound out today (p. 144).

Historical and political nonfiction, then, might just be the platonic ideal of this usage of language. The best nonfiction, in my estimation, unearths and strings together previously unknown or unrelated ideas or events into cohesive strands with commentary on what the connections mean—but the cherry on top are the wealth of sources cited and available to reference for further research. Visual supplements, like graphs or diagrams, or pictures of people and places and subjects are helpful, but their presence or lack thereof isn’t a hindrance, either.

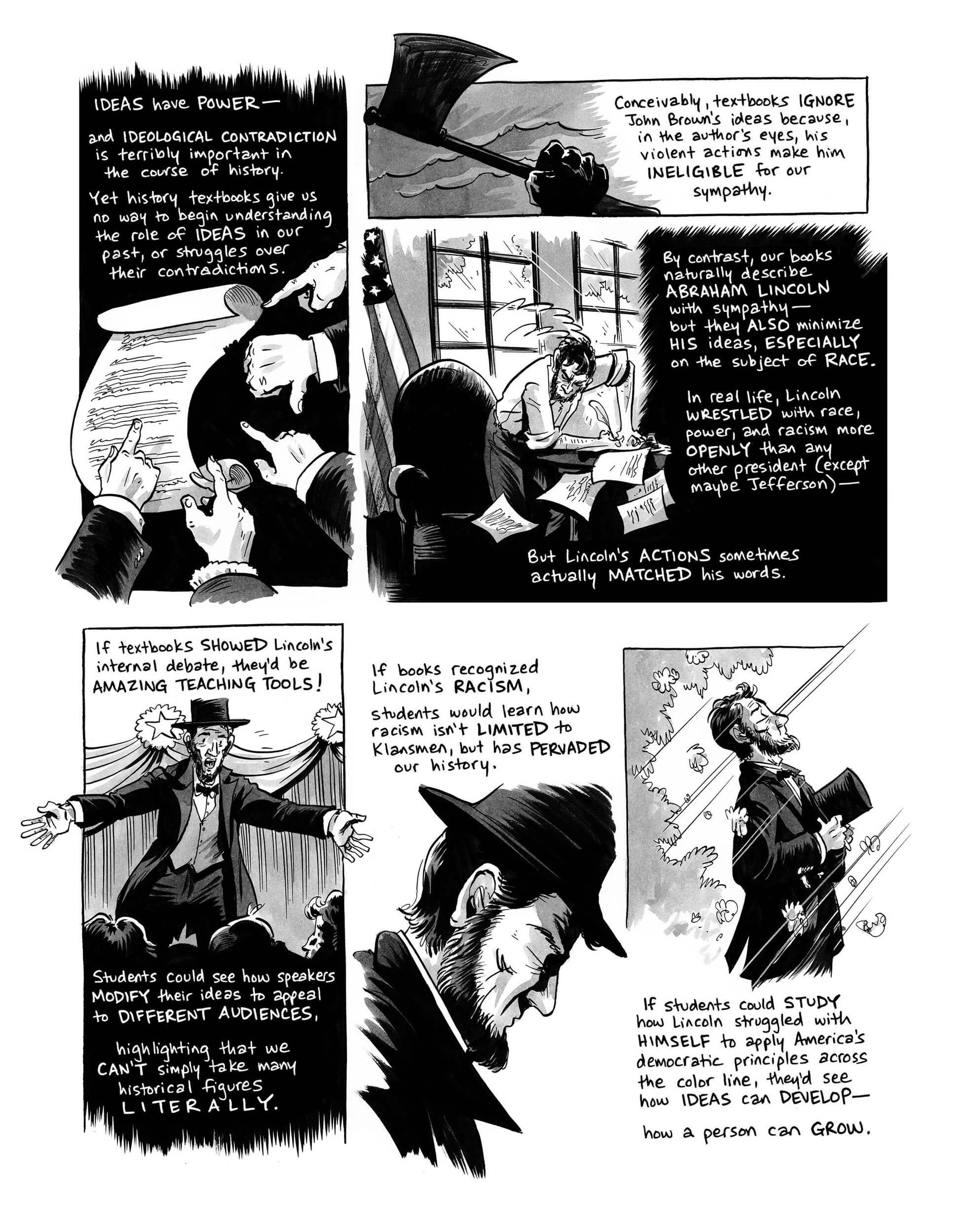

Perhaps that makes it more ironic how much more readable I found the version of a book that uses both words and pictures together instead of just the former: the recently released graphic adaptation of Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbooks Got Wrong (2024). Originally written by James W. Loewen nearly 30 years ago, this graphic adaptation, done in collaboration with Nate Powell, takes a 446-page book cutting through the mythologies of American history peddled by the country’s educational material, with all the quotations and refutations and citations that entails, and in Powell’s words, “[rewrites] and [streamlines] it in five separate rounds before a single panel of artwork was finished” (p. 262). The fully-illustrated result is a 264-page work of graphic nonfiction that retains the essential text of the original book, while supplementing that text with faces to attach to famous and obscure names, renderings of notable places and people, visual metaphors to drive home the textual ones, and more in sequential form to augment a reader’s retaining of the material. That reader is likely from a much wider age bracket than any of its two traditional audiences—anyone who read the Lies My Teacher Told Me around its original publication are up to three decades older, after all—but that audience had already been expanded to teens through a young readers edition published in 2019. With the addition of Powell’s graphic adaptation, Lies My Teacher Told Me is able to reach its widest range of readers, be they curious adults in hindsight such as myself, or a teenager encumbered by the lies and can’t be bothered with another text-based tome otherwise.

I portray historical nonfiction as unconventional among comics, but as I’m sure a lot of us here can attest to, that’s for the historical kind. Nonfiction on a personal level—memoirs, biographies, and the like—have been a staple of comics for all ages for a long while now. And they can certainly be detailed in their own way, not only from pulling techniques from fiction or the author situating their lives in a historical context, but from how deeply authors can mind and mold the depths of their own life events.

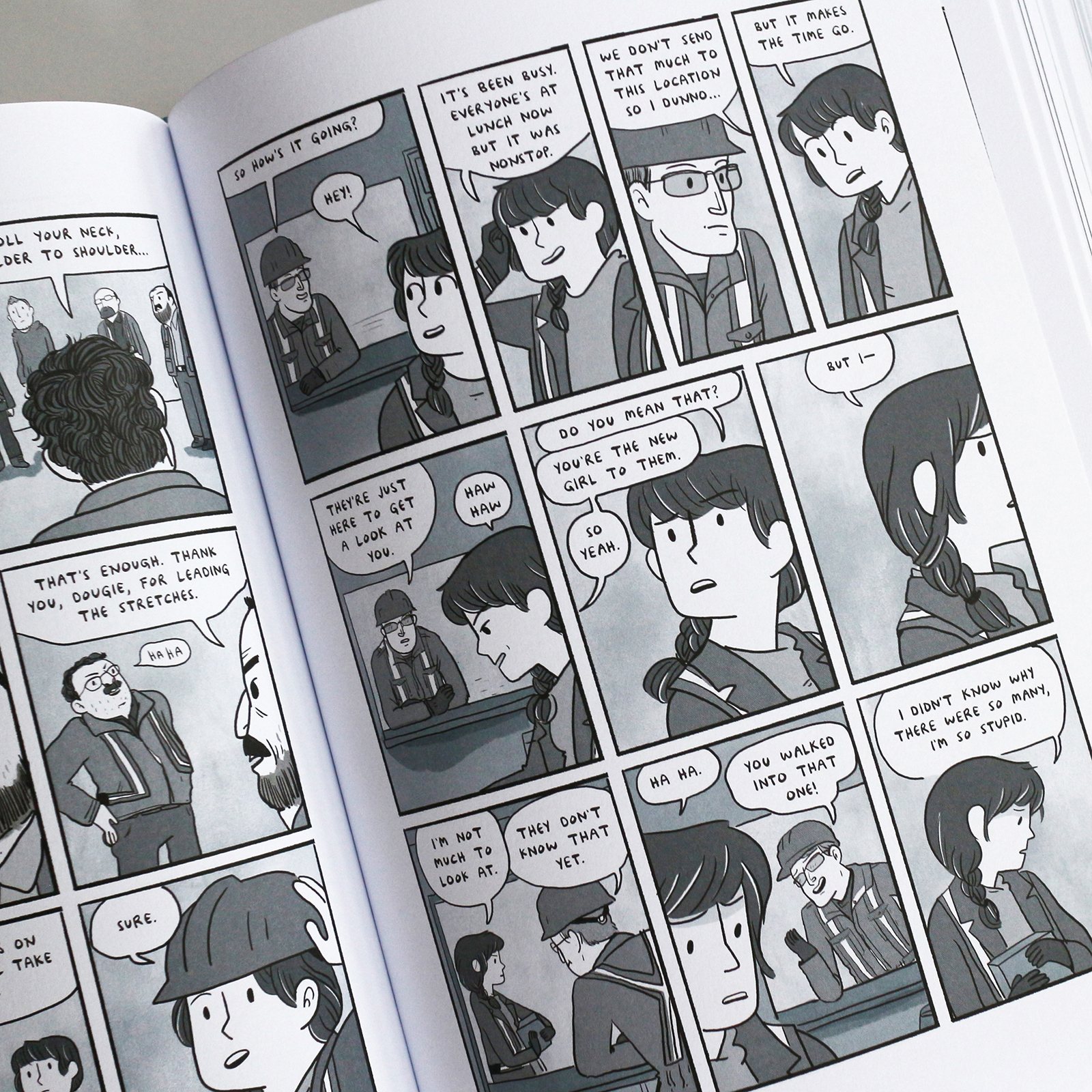

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands (2022), an autobiographical graphic novel by early-aughts webcomic artist Kate Beaton, firmly situates itself within the latter camp. Hark! A Vagrant, Beaton’s name-making webcomic parodying historical people and phenomena of western history, features an flippant, offhand art style resembling a teenagers’ irreverence, one that is preserved in Ducks—but Ducks’ subject matter bends it towards something for more mature readers. Patching together a massive scrapbook of vignettes from her pursuit to pay off her undergraduate student loans, Beaton follows the siren song of a gold rush far from her coastal home to the Canadian oil sands and finds herself navigating the bruising dynamics of being a woman in an overwhelmingly male-dominated environment on the edge of society.

While the narrative is bookended by her departure and success, Ducks reads like another webcomic or perhaps a comic strip, with sequences never stretching longer than four or five pages, and immediate transitions from one episode to the next with little labeling or establishing shots to separate them. Though nothing identifies it as such, Ducks almost feels like a coming-of-age story—it’s slight enough that it might be the result of my perception, but Beaton proportions her cartoon self ever-so-slightly-shorter than her male coworkers until the very end of the novel, with her loans paid off and no need to remain in the sands. There’s very little closure to be had, though, as Ducks isn’t a traditional narrative with clearly identifiable narrative beats or a nutshell takeaway. The themes you’d expect are there, of course—sexism and gendered violence, economic precarity imposed from the top-down, the effects of living isolated environments on people—but it’s hard to separate any one strand from the other. Here is a fresh-faced young woman, thrust into a specific disarray of 21st century life, and here is the record of her life and the people that she saw, simply as they are. That, I think, is key to what makes Ducks worthy of all the fanfare that originally drew me to it—as Beaton writes in the afterword, “I learned you can have good and bad at the same time in the same place, and the oil sands defy any easy characterization” (p. 433).

References

Beaton, K. (2022). Ducks: Two years in the oil sands. Drawn & Quarterly.

Drawn and Quarterly. (2024). Ducks interior [Online image]. https://drawnandquarterly.com/books/ducks/

Loewen, J. W. (1995). Lies my teacher told me: Everything your American history textbook got wrong. Touchstone Books.

Loewen, J. W. & Powell, N. (2024). Lies my teacher told me: a graphic adaptation. The New Press.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. William Morrow.

Wilson, J. (2024). Nonfiction graphic novel selections [Photograph]. CC BY-NC-SA.