Graphic Novels Discussion #3: Manga

3 June 2024

Read the manga you've chosen and answer the following questions.

• Tell us the story of how you found your title/material (BRIEFLY). What resources helped you pick your material (make sure to cite appropriately!)? What helped you determine it was "______” (in the genre you’re focusing on, in the format you’re exploring, etc.)?

• Who is the target audience? How can you tell?

• What is the title/material’s appeal? How does it appeal to its target audience?

• If it is a diverse title: Identify the communities to which the primary character(s) belong(s). Does the author belong to the identity represented? If not, how accurate is the portrayal to the best of your knowledge? Seek out reviews, blogs, etc. to help with this assessment.

• Was your experience reading manga different from what we think of as more "traditional" graphic novels? If so, why do think it was?

Ah, manga. If even American-made comics have historically been derided as base literature, then comics from Japan might as well be foreign artifacts made more enticing because of their unfamiliarity, even today. Fortunately for me, I came of age right when manga and other Japanese media began their meteoric ascent into pop culture and subsequently seep into its artistic traditions. As distinct as the average person or even older comics reader might find them, manga and anime and Japanese role-playing-games and music and the language itself and all their collective cultural standards have claimed a sizable stock of real estate in my head to make those sensibilities appear practically invisible.

Of course, as a boy who had little interest in anything not oriented towards boys until relatively recently, there is a very narrow range of manga and Japanese media that I engaged with. If flashes of brightly-colored fantasy characters engaged in over-the-top violence come to mind when you think of manga or anime, the Narutos and Demon Slayers and My Hero Academias and the like, then you’re thinking of shonen media, which is specifically created for an audience of adolescent boys. This is usually the only kind of manga that comes to prominence in pop culture—which might just be expectedly ironic depending on what the audience makeup is. Current statistics on the gender demographics of manga readers are hard to find online, but in a Publisher’s Weekly article citing the founder of manga publisher Tokyopop from the early aughts, Reid (2003) reports that 60% of American manga readers were female. Compare that to the (pre-pandemic) average circulation from Shueisha, Japan’s largest publisher: Weekly Shonen Jump, which serializes all three of the titles listed above in their homeland, moves around 1,740,000 million copies each month—while Ribon, the equivalent magazine for shojo, or adolescent girls, manages a diminutive 145,000 copies, less than 10% of its male counterpart (Hodgkins, 2019).

All this context is to establish how I and most gaijin devotees of Japanese media likely have next to no exposure to manga made specifically for girls, thanks to all the usual reasons explainable by reading any reputative work on feminism.1 So for this week’s reading, I deliberately picked up a shojo manga for the first time with Sorata Akiduki’s Akagami no Shirayukihime, or Snow White with the Red Hair.

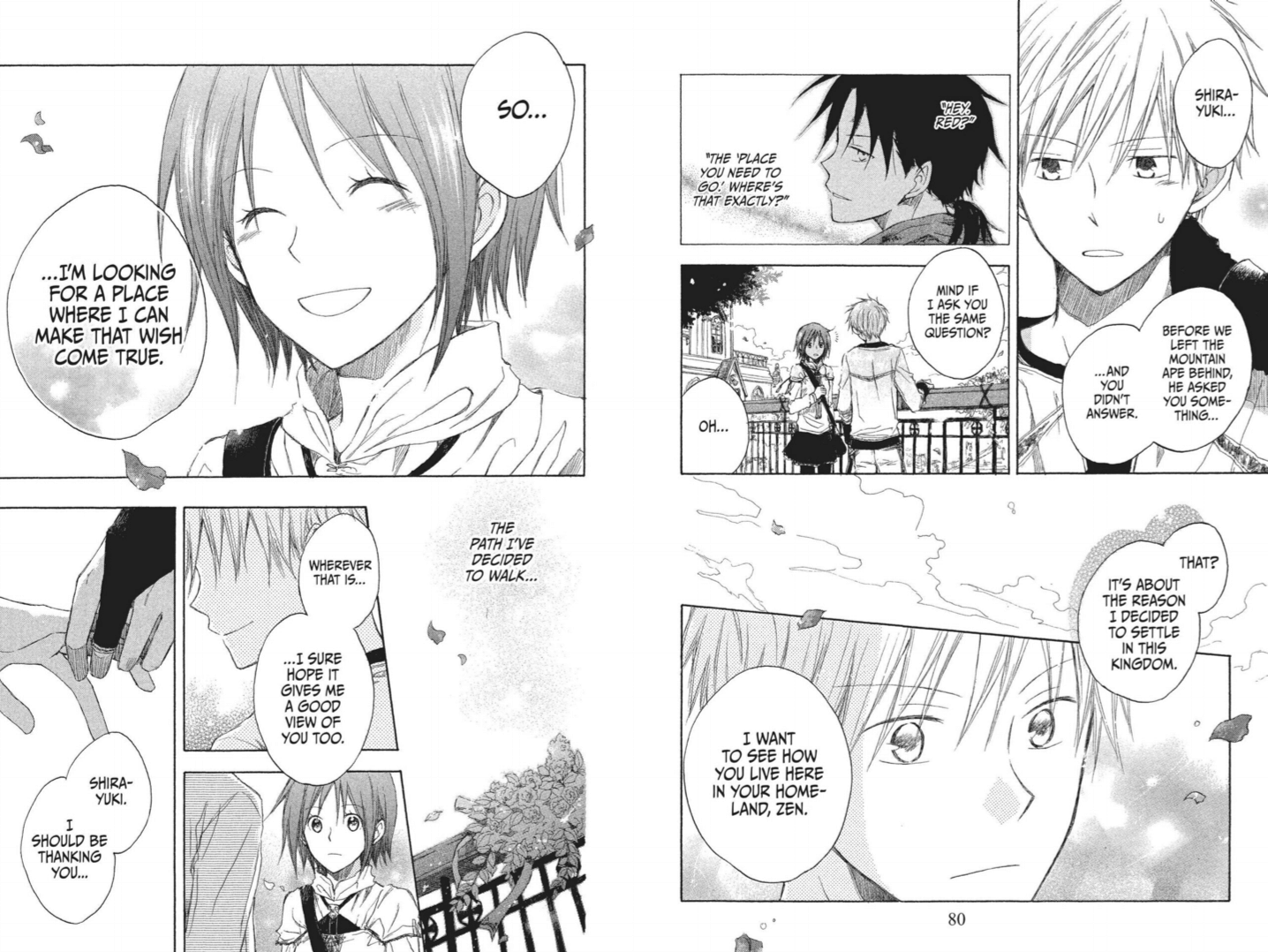

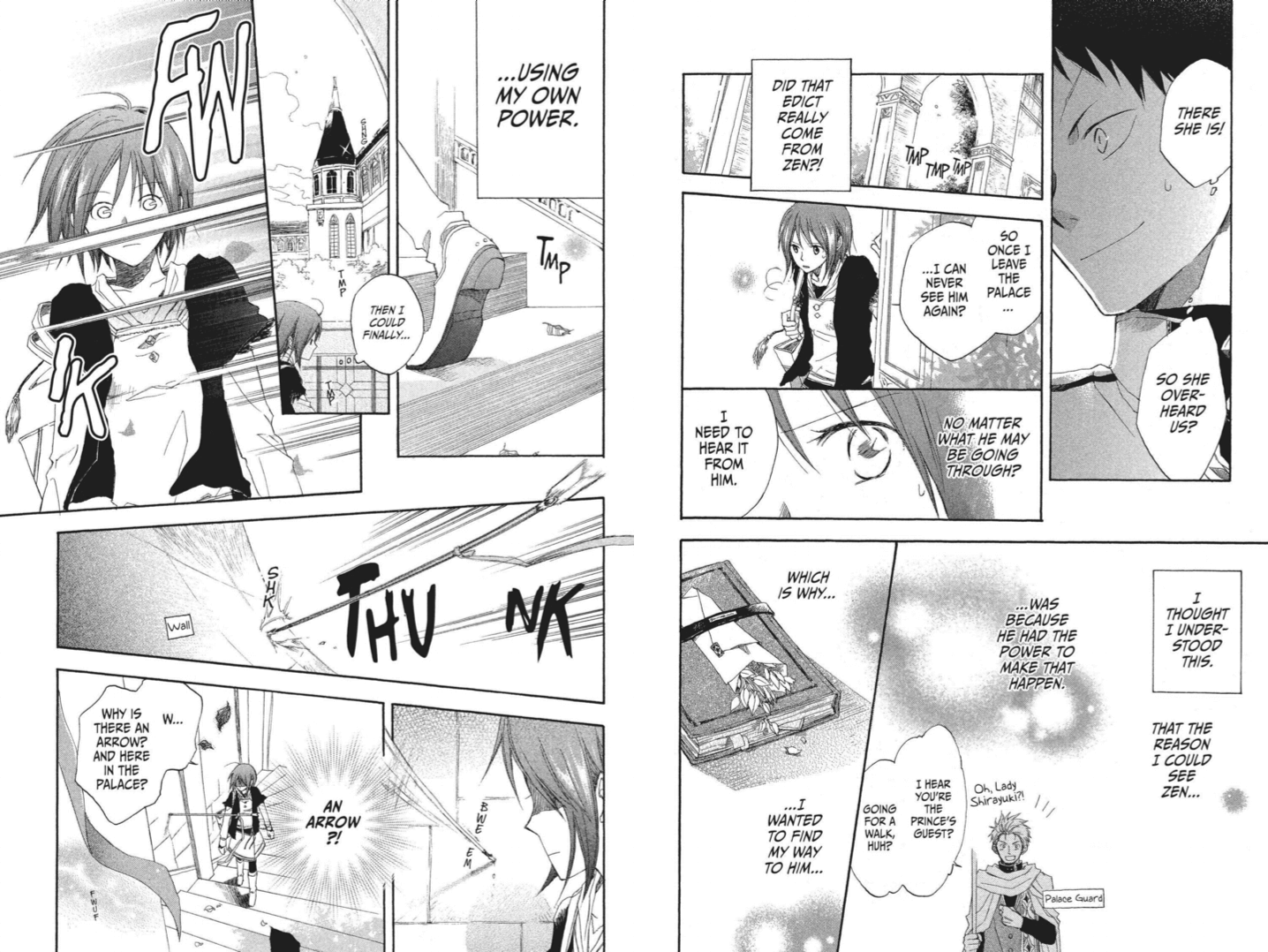

As is typical of gendered expectations, physical conflict usually isn’t the driving force of shojo manga. Instead, the interpersonal dramas that usually accompanies those conflicts takes center stage—readers must follow the internal, emotional and/or psychological development of its characters to make sense of shojo narratives (Masuda, 2017). This leads to a lot of fragmentary panels of areas and everyday objects and characters’ eyes and/or other body parts common across the entire tradition of manga (McCloud, 2006, p. 216), pondering and poetic internal monologues of characters’ feelings, and this peculiar use of these glowing motes and other particles to evoke emotional crescendos, among other techniques. Since a lot of shonen manga eventually succumbs coheres to villain-of-the-week storylines that lack much thematic resonance or anything more than superficial spectacle (looking at you, Frieren), I found this a welcome change from my tastes as an unseasoned juvenile.

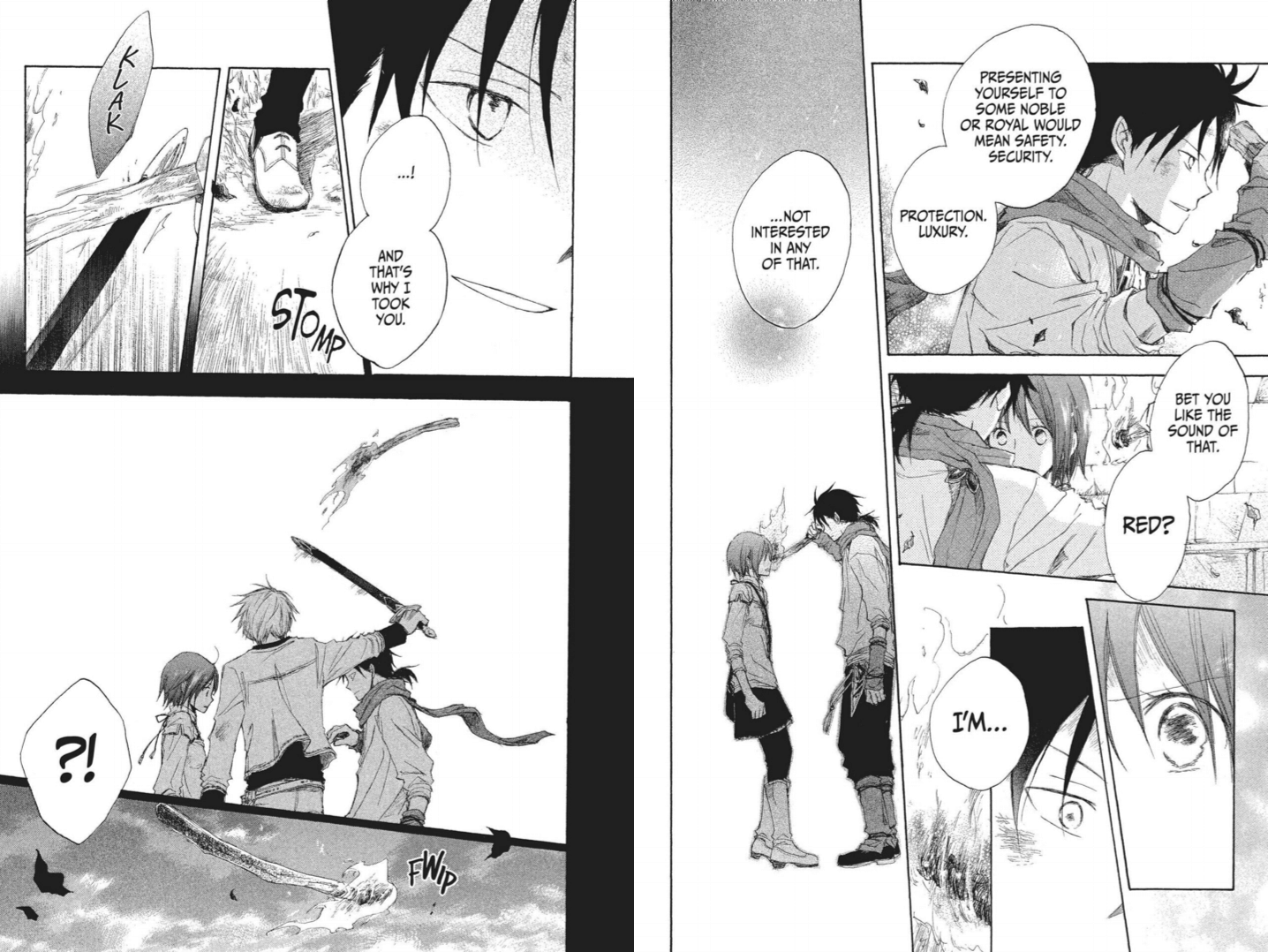

That doesn’t mean physical conflict is entirely absent from shojo manga—and in Snow White with the Red Hair’s case, the threat of it directed towards the titular character propels things forward, at least in the first volume. Shirayuki, the main protagonist whose name is a literal compound of “Snow White,”2 begins with her becoming the target of not ire from a jealous queen, but the covetousness of the prince of her home kingdom, thanks to her apple-red hair. Shirayuki flees into the forest, has a chance encounter with a young man, Zen, and his pair of companions. With the help of this dashing stranger, who turns out to be a prince from another kingdom, Shirayuki is able to evade the machinations of the men seeking to constrain her—and so begins her tale to carve out her own path through life…supposedly.

While many of the situations she finds herself in usually require Zen’s assistance by the end, Shirayuki is written with a remarkable self-assurance, showing indignance to the men around her and devising ploys to escape her binds all on her own. Flattening summations of “strong female character” aside, this also makes for an intriguing, perhaps even feminist bent to the moniker Snow White—instead of the unknowing desirability of her namesake, Shirayuki is compelling simply for being an already desirable woman willing to reject those making their advances and assurances without her input.

But alas. As interesting as Snow White with the Red Hair is conceptually, it manages to fall into very similar pitfalls of its shonen counterparts. As typical of most narratives involving an innocuously amusing meeting of a potential love interests minutes into the opening act, Snow White with the Red Hair is a fantasy romance, and any secondary intrigue is ultimately intended to dripfeed into Shirayuki’s supposed love affair with Zen. Which isn’t a sin on its own at all, given that’s all but written on the genre tin; yet like no small number of its contemporaries, the supporting characters and especially the world the manga is set in are given such threadbare development in this first volume that they seem like little more than background props. In fact, the plots of the initial three out of these four chapters are almost complete repeats of each other: Shirayuki is hounded and/or kidnapped by some other twink guy insisting that she either belongs with him or doesn’t belong somewhere, before Zen appears to save her or spur her towards a resolution.

This might just be too harsh criticism for being disappointed that an apple tastes like an apple. Maybe even ironically so, because this manga clearly has no small audience, given that my interest in Snow White with the Red Hair was piqued by how regularly its volumes pass through my hands at work. It’s certainly not a unique criticism, either. Shojo and the wider landscape of women’s comics across ages allow for girls and women to see their own lives in positions where talent and originality matter, yet these comics do not always “encourage women to be independent […] and to fight traditional, patriarchal values” (Ogi, 2003). As Snow White with the Red Hair occasionally evinces though, individual shojo media can hew towards both poles at differing degrees—and ultimately, any considered writing about the genre must remember that “the concept of shojo, therefore, is not only an imposed idealized construction, but also a means embraced and manipulated by girls themselves” (Monden, 2019).

1 ^As is succinctly surmised in this social media thread: maybe there's a reason that anime aimed at boys gets exports and dubs and live action remakes and DVD releases and continuous attention and 16 seasons and becomes a global culture sensation, and anime and manga aimed at women is generally given like, a single english sub and does not escape its little sphere.

2 ^Shira (白) for white, plus yuki (雪) for snow. Amusingly, a literal translation of the title Akagami no Shirayukihime would be "Red-Haired Princess Shirayuki," which would likely confuse readers in translation given that Shirayuki isn't a princess by birth.

References

Akiduki, S. (2019) Snow white with the red hair. Volume 1. VIZ Media.

Hodgkins, C. (2019, April 22). Shueisha reveals new circulation numbers, demographics for its manga magazines. Anime News Network. https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2019-04-22/shueisha-reveals-new-circulation-numbers-demographics-for-its-manga-magazines/.145991

Masuda, N. (2015). Shojo manga and its acceptance: What is the power of shojo manga? In Toku, M. (Ed.), International perspectives on shojo and shojo manga: The influence of girl culture (1st ed., pp. 23-31). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315749976

Monden, M. (2019, February 22). A dream dress for girls: Milk, fashion, and shōjo identity. In Berndt, J., Nagaike, K., & Ogi, F. (Eds.), Shōjo across media: Exploring "girl" practices in contemporary Japan (pp. 209-231). Springer.

McCloud, S. (2006). Making comics: Storytelling secrets of comics, manga and graphic novels. William Morrow.

Ogi, F. (2003). Female subjectivity and shoujo manga: Shoujo in ladies’ comics and young ladies’ comics. The Journal of Popular Culture, 36(4), 780-803. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5931.00045

Reid, C. (2003, October 20). Manga is here to stay. Publisher’s Weekly, 250(42). https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/print/20031020/27926-manga-is-here-to-stay.html